The brand new monthly column from celebrated US-based ‘A-List’ session musician, hit songwriter, successful producer and one-time Rolling Stone magazine music writer, Jon Tiven.

Lifting the lid off the serious (but fun!) business of making music in the studio and on the road, with some fascinating “I was there” recollections of the ‘who’s who’ of stars he has worked with across more than four decades…

As this is my very first column for Music Republic Magazine, I am going to assume that many of you will be unfamiliar with me, so here is a short version of my musical history…At four-years-old, I learned piano and at 10 I switched to sax’. At 15, I was hit in the mouth with a baseball bat while playing catcher and 21 stitches later I became a guitarist.

Having written for science fiction fanzines when I was 11, at 12-years-old I started my own rock fanzine The New Haven Rock Press in 1967, and soon began writing for Rolling Stone, Fusion, Melody Maker, and other periodicals.

In 1974, I made my onstage debut with Big Star at Max’s Kansas City, and a year later I was hired by Chess Records to do publicity and A&R. In 1975, I made my recording debut, playing congas on the Rolling Stones’ “Metamorphosis” album (“Jivin Sister Fanny” and “Goin Down”) produced by Andrew Loog Oldham.

I exited Chess later that year to produce Alex Chilton’s debut solo effort, “The Singer Not the Song”, in Memphis, to be released a year later. I was in and out of the early punk rock/New Wave indie label scene, as a partner/staff producer at Ork Records and later Miracle and Big Sound.

Formed my own band The Yankees, and eventually decided to concentrate on writing songs. I was given the opportunity to produce a series of tribute records to the songs of Don Covay, Arthur Alexander, Otis Blackwell and Curtis Mayfield; which spawned not only great notices, but bonafide Top Ten hits.

After the Jeff Healey Band took my song “River of No Return” (written with my wife Sally and the brilliant lyricist Keith Reid) to triple-platinum status and Huey Lewis & the News struck gold with “He Don’t Know” (which my wife and I wrote with soul legend Don Covay), people began to take me seriously as a contemporary R&B/blues producer/writer in the mould of my friends/heroes/collaborators, Dan Penn, Jerry Ragovoy and Steve Cropper.

Producing the legends…

I was called upon to produce and co-write a series of albums by Wilson Pickett, Don Covay, Little Milton, and Sir Mack Rice, that would give each of these vets a victory lap in their later years.

But I would not let myself be pigeon-holed, and developed strong relationships with Frank Black a.k.a. Black Francis and the late great P.F. Sloan, producing work with both of them that would bring them great acclaim. I brought Steve Cropper and Felix Cavaliere together, for a joint project “Nudge It Up A Notch”, later producing a record by Steve paying tribute to his heroes, The 5 Royales.

Billie Ray Martin and I made a record together, “The Soul Tapes”, that went Top Ten on the dance/club charts in 2016. Most recently I discovered a great young singer/songwriter named Dylan LeBlanc, who is finding his way into people’s hearts, and I have partnered with lyricist Stephen J. Kalinich (who wrote the words to the Brian Wilson/Paul McCartney duet “A Friend Like You”) for a series of collaborative records.

The latest of which, “Scrambled Eggs”, is to be released on Record Store Day; April 20th 2018, and features Mr. Kalinich singing duets with Black Francis, Bekka Bramlett, Ellis Hooks, and Dylan LeBlanc.

I hope I dropped enough names so that someone you are interested in was mentioned! I am here in order to impart news, knowledge, inside info, or any sort of wisdom that only I am privy to; or at least that is what they told me when I signed up. So I would like to start by giving you the skinny on what I did to cut my baby teeth, and how I learned to make records.

I attended every session I could, did my impersonation of the fly on the wall. I had friends who were producers – Andrew Loog Oldham, Tony Visconti, Shadow Morton, Jerry Wexler, for starters – and I watched them and took it all in.

Talking is not the point, listening is the point. I learned that once at a session at which I was a participant, not just an observer. I was playing guitar on a Don Covay session and it was me, Don, Bobby Womack and the engineer Jimmy Douglass.

Shut up or else!

Don had made me musical director for his band in 1987, and we did some wild gigs, making enough noise to attract the ear of Chris Blackwell. When he made his record for Island in the early 90s, Don made sure I was in on a lot of it, and I was given a fair amount of responsibility.

At this particular session, Don was having trouble communicating to Jimmy what he was trying to accomplish technically, and they were going around in semantic circles. I had cut the original demo, so I knew how I’d got the sound originally, and interjected what I thought would be an easy solution. Don turned to me, giving me the stink eye. He then pulled a pistol out and sat it on the console. “You are here to play, not to talk.” I didn’t make that mistake a second time. Sometimes you gotta keep your head down!

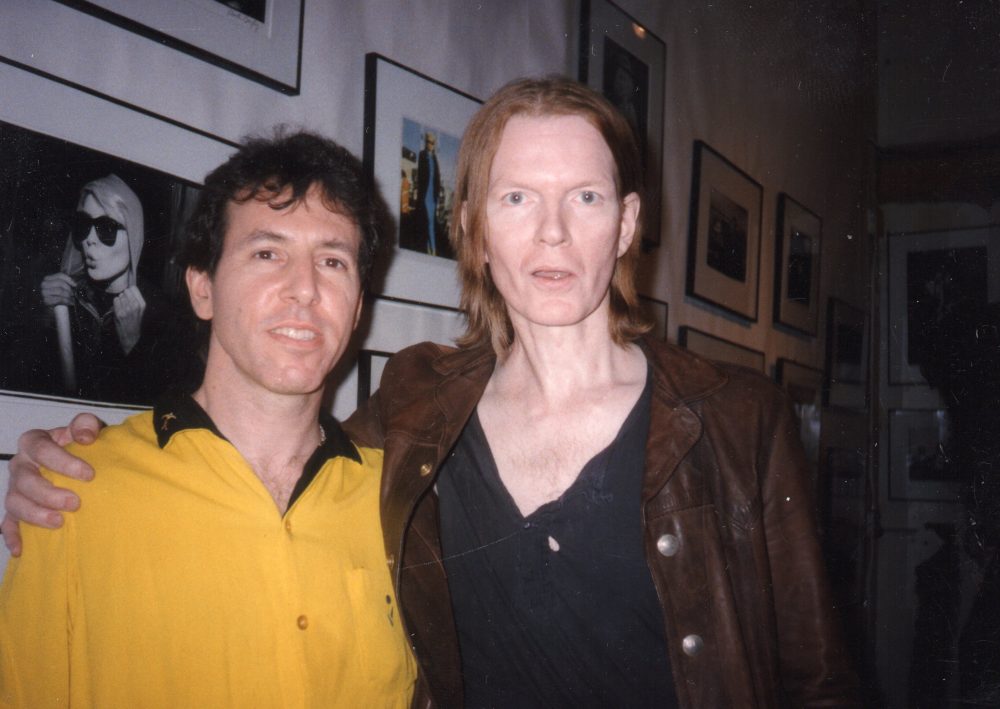

I participated in many sessions that were not magical, some outright painful, but I made sure all of them were learning experiences. When I joined The Jim Carroll Band for their second album “Dry Dreams”, it should have been magical. The first album had been engineered – and pretty much produced – by Bob Clearmountain, who is a one-of-a-kind talent.

As in many cases like these, the production credit had gone to manager Earl McGrath, who might have been able to make it in the movie business as a producer, but not in the record business, and that’s being kind. Clearmountain had differences with Earl and bowed out of making the second album, leaving it to Atlantic staff engineers Dan Nash and Gene Paul to fill his shoes.

Bob Clearmountain had distinguished himself making sense of Rolling Stones’ tracks cut in the dead of night, with a thousand guitars to sort through. Whereas Dan and Gene had been used to cutting with people like Bernard Purdie and Jerry Jemmott; laying down a spare and sophisticated rhythm that merely needed bit of sculpting.

The Jim Carroll Band was at its best a careening ball of energy, and we considered a track a take, if everybody ended up in the same place and there were no glaring rhythmic errors. Countless hours in the studio failed to capture the excitement of the artist, as Earl couldn’t be bothered to absorb even a basic comprehension of how a bassist and a drummer work together, never mind perceive the difference between a rhythm and a lead guitar.

His way of dealing with this was to try to keep everyone guessing as to his master plan, and when the record was finally played to the band, we couldn’t believe our ears. We figured he was the producer, he would find a way to make things work, even though the rough mixes sounded like chickenshit. The final mix, alas, was no chicken salad. I was reminded of my old friend Ritchie Blackmore’s comment, when he heard one of his records: “They’ll fix it in the stores.”

These days, if a producer or a studio owner says he’s got a magic mojo, I immediately get suspicious. Music is about people and their ability to communicate with their instruments/voices/words/notes, and of course the space that these vibrations inhabit is important, but not paramount.

Working with the King…

I’ve made great records in studios that were more a matter of convenience than choice, and I’ve been party to records made in the most fabulous studios that I wouldn’t waste a second thought on. If you’ve got the goods, you can convey it in your bathroom. Which reminds me of a story, and then I’ve got to go…

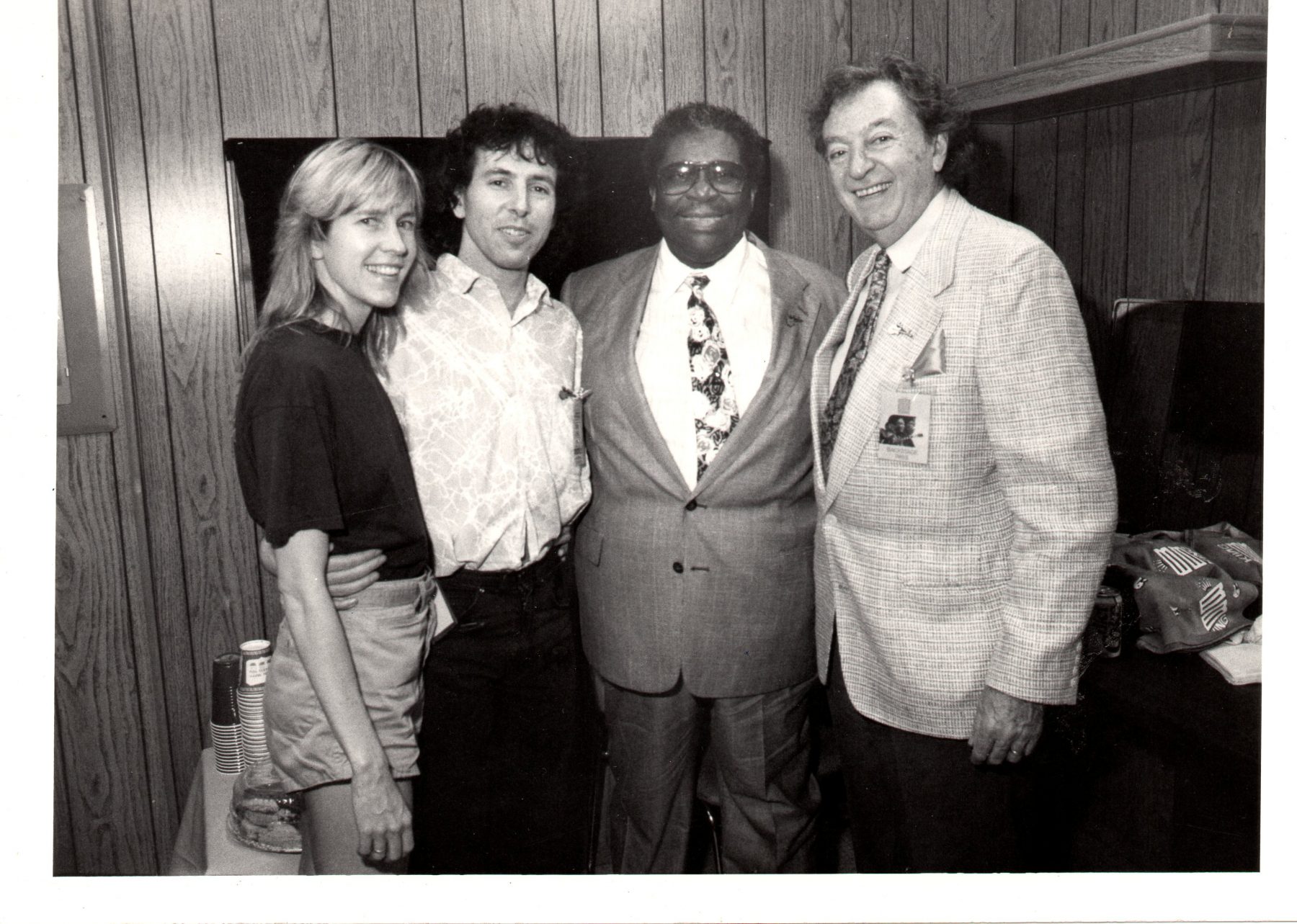

Shortly after my “River Of No Return”/Jeff Healey Band success, I ran into an acquaintance who offered to show my work to B.B. King’s manager, and of course I said go forth and conquer. A few weeks later my phone rang and sure enough it was Sid Seidenberg on the line, expressing his interest in the songs presented for his artist, the one and only B.B. King.

“But,” Sid interjected, “B.B. only records songs that haven’t been recorded before, and these are obviously records.” “Mr. Seidenberg, those are demos I made in my studio apartment with me playing everything,” I replied. There was a short pause. Then, his retort. “How would you like to produce B.B. King?”

The rest is history, but another story entirely. I’ll save that for a later date. See you next month…

By Jon Tiven

Images:

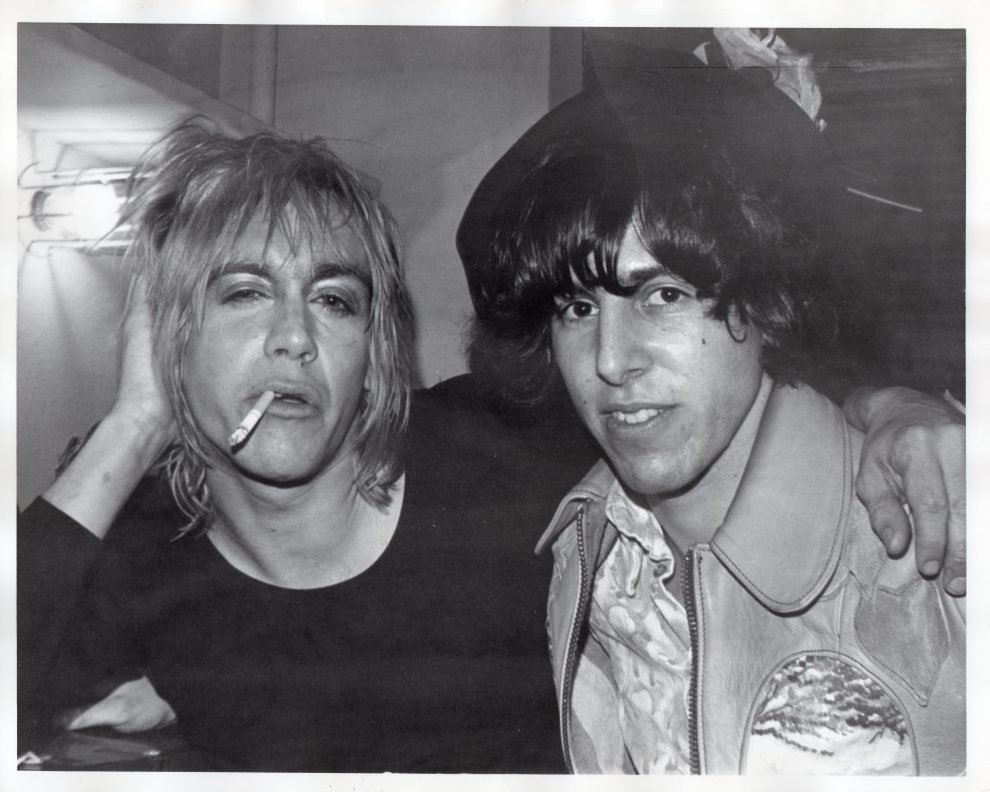

Main photo: Iggy Pop and Jon Tiven – 1974 (Credit: Seth Tiven)

Bottom photo: Sally and Jon Tiven, BB King and Sid Seidenberg – 1990 (Credit: Chuck Pulin)

Sax shot: Jon and his alto – Circa 1966

Small – yellow shirt, sat with guitar – photo: Jon Tiven 2003

Jon Tiven (yellow shirt) and Jim Carroll (brown jacket/black shirt)